Representatives from 190 nations will assemble on November 30 in Paris for the annual UN Climate Change Conference. Scheduled to conclude on December 11th, the Conference is expected to attract over 25,000 official delegates and more than 50,000 participants, making it one of the largest conferences ever held in France.

Representatives from 190 nations will assemble on November 30 in Paris for the annual UN Climate Change Conference. Scheduled to conclude on December 11th, the Conference is expected to attract over 25,000 official delegates and more than 50,000 participants, making it one of the largest conferences ever held in France.

With the impacts of a changing climate more apparent, hopes for a successful conclusion appear higher than for previous conferences. The ambitious goal for this conference is to achieve “a legally binding and universal agreement on climate, with the aim of keeping global warming below 2°C”. But, how realistic is this goal?

The Conference will be held in Le Bourget, a suburb of Paris and home of the Paris Air Show. The site will host not only the official UN conference but also several hundred “side events” (typically 2 – 3 day forums) presented by climate change and environmental organizations. A general, “overview” schedule of the conference can be found here.

In addition to the conference hall, the site will also include such facilities as offices for UN officials, 32 “negotiating rooms”, a press center designed to accommodate the needs of nearly 1,000 press representatives, and display pavilions open to the public. Hosting a COP is truly a major undertaking for a host country and must be doubly so for France during these troubled times.

The upcoming conference is also referred to as the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP21/CMP11). COP is the acronym for “Conference of the Parties”, the 195 countries who are party to the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), while the CMP11 denotes the 11th annual meeting of the countries who are party to the Kyoto Protocol established at the 1992 COP in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The initial “Earth Summit” conference in Rio de Janeiro was probably the most successful of the of the UN Climate Conferences in that it established climate change as a global threat; created the framework for cooperative, international action to address climate change, and established the goal of a 2oC maximum permissible global temperature increase. Progress at succeeding COPs has generally been significantly less.

While the results of COP19 (Warsaw, Poland) and COP20 (Lima, Peru) were disappointing, they are now viewed as essential steps towards COP21. One outcome of COP19 was the establishment of a new scheme for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by participating nations. Rather than a “top-down” approach establishing emission targets, each nation was invited to submit an “Intended Nationally Determined Contribution” (INDC) prior to COP21. COP20 refined this approach and added structure. The “bottom-up” approach for the development of national emission targets seems to have been successful as submissions from 149 nations has been received as of this writing (November 24th). The submissions for each nation can be found here.

A great deal of effort and preparation has gone into making COP21 a a highly successful conference, and the INDC process has been highly successful in obtaining participation and public statements of intent; however there are also a number of reasons for concern.

1.) Are the INDCs adequate?

The framework for INDCs calls for the proposed reduction of emissions to be initiated by 2020 and extend through either 2025 or 2030. A common emission baseline of 1990 was also suggested, but many nation’s INDCs used alternate reference dates, such as 2005, 2013, and BAU (business as usual). The greenhouse gases included in the INDCs also vary between nations, with some only including CO2, while others include many other gases. And, the units of measurement vary between submissions, with some INDCs quantifying emission reductions on a national basis, and others basing their intended reductions on GDP or per capita, which in contrast to the absolute value of a national base will result in a base relative to a changing economy and an increasing population. Thus it is extremely difficult to compare individual INDCs and project long-term results.

The INDC process required the UN to produce a synthesis report of submitted INDCs by November 1, 2015 which can be found here. The “Brief Overview” document of the Synthesis Report includes this summary graphic to illustrate the the conclusion that the proposed INDC’s will only slightly slow the rate of emission growth, rather than stabilize, or reduce, emissions.

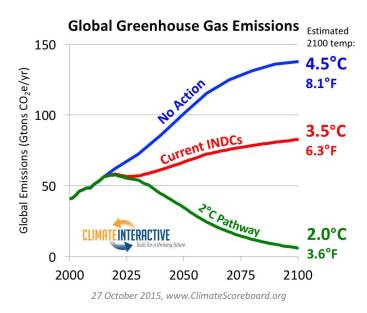

Climate Interactive has done a more in depth analysis of the INDCs, using their C-ROADS model, which projects the estimated results to 2100. The graphic below is a summary of their findings; a more detailed graphic includes four levels of action that could be taken when the current INDCs expire, including a path to 2oC.

The Climate Interactive analysis has been widely used, including an interesting presentation by the New York Times.

2.) Conditional INDCs

A number of the INDCs were submitted as “conditional”, leaving open the question of whether they will ever be implemented, or to what degree they will be implemented. COP16 (Cancun, Mexico) formalized the “Green Climate Fund” with the objective of raising $100 billion by 2020 to assist developing nations with mitigation and adaptation. To date a little over $10 billion has been pledged, and fewer funds actually received. For example, the U.S. which has made an initial pledge of $3 billion was the largest, has yet to actually provide any money to the fund, and the Republican dominated Congress again removed funding from next years budget. Other nations whose economies are in recession may also defer filling their pledges. Therefore, INDCs conditional on receiving funding from the Green Climate Fund may be dubious.

3.) Increasing fractions and special interest alliances within the Delegates

Past COPs have seen increasing tension between the developed nations, responsible for most emissions into the atmosphere, and the developing nations who are being disproportionately impacted by a changing climate. This tension has recently resulted in a number of regional and special interest alliances, whose numbers seem especially high among this years delegates. Finding a common ground between the various parties may prove to be a Herculean, but necessary, task.

4.) Over reliance upon forest lands to sequester carbon

Like many others, the U.S, INDC includes the preservation of forests as a means to reduce CO2 emissions. This reliance on forests as to sequester carbon has been called into question as a result of a recent study by U.S. Forest Service researchers which projects a 35% decrease in the ability of U.S. forests to sequester carbon due to aging forests and disturbances such as fire and insect epidemics. While the study did not include the forests of Alaska due to limited data, it is likely that these forests have, or will soon join the forests of the Rocky Mt. region as carbon sources due to increasing fire, and the melting of permafrost in the vast peatland forests of Alaska. As the planet warms nations around the globe are seeing an increase in both the numbers and intensity of forest fires. Many of these fires are now so intense that the soil organic matter is volatilized and the mineral layer literally baked into a hard pan that will prevent forest regeneration for some considerable time. In the long run, it is likely that the only forests that truly sequestered carbon are those that we are now burning as fossil fuels.

5.) Under reported emissions

China recently reported that it has been consuming about 17% more coal than previously estimated, and amount equal to about 70% of the U.S. total annual coal consumption. The error resulted from unreported data primarily from carbon intense small businesses. The impact of this error is huge, initial calculations estimate that China has emitted almost one billion tons more of carbon dioxide a year since 2000 than previously estimated. The annual difference is greater than the total, annual carbon dioxide emissions of Germany.

Envoys from various nations have been meeting frequently over the past year to iron out differences and prepare targets for consideration at COP21. Much of that work will be impacted by China’s new data. Researchers are now faced with the question of what happened to this vast amount of CO2, where did it go? And then many of the computer models will have to be revised. Meanwhile, additional uncertainty has been added to any targets established at COP21.

It seems clear that even full implementation of each of the submitted INDCs will do little more than temporarily slow the rate of emission increases, which will surely result in a warmer planet. We can hope that the INDCs and any other targets accepted at COP21 are viewed as a starting points, not a status quo to be maintained until 2030 when more stringent emission reductions would be required, and well might be too late.

COP21 is scheduled to end on December 11th. If history is any guide, the sessions will be extended and a final compromise agreement not reached until the early morning hours of the 12th. If this history is repeated at COP21 we can hope that any last-minute agreements not reached just for the sake of appearance, but rather for the good of the planet.